In Nadim Damluji’s presentation — “The Violence of Localizing Western Comics for Arab Children” — he began with a slide boiling down recognizably (North) American, European, and Japanese comics. There might well have been a fourth slot on the slide with “Arab” and a question mark over it.

Damluji said that when he first began investigating Arabic comics, he saw two distinct periods in production: An early period where distinctly Arab comics were being produced and a shift in the 1960s to translated works. Damluji said that his view has changed, and that he nows sees an exchange between Arab and translated comics, noting for instance a “resistance in translation” when it came to Samir’s translation of racist moments in Tintin. But he still said that we “can’t escape the fact that American comics may have pre-empted a wholly Arab form of comics.”

After Damluji, Lina Ghaibeh spoke about an element that’s unfortunately central to many Arab comics for children: “Propaganda in Comics in the Arab World: From Nationalism To Religious Radicalism.” Ghaibeh also gave a similar talk last year, which is available on YouTube, following a path from nationalist propaganda in state-sponsored comics to religious propaganda in privately-sponsored comics by bother Christian and Muslim groups.

Although Arabic children’s comics began with fantasy story lines, by the 1960s and 1970s, “The idea of Arab nationalism affected every aspect of the comics,” including, Ghaibeh said, the choice of Modern Standard Arabic over a colloquial. In a more recent Jordanian Islamic comic, the “bad guys” spoke colloquial while the “good guys” used a classical Arabic.

Through the middle of the twentieth century, Arabic comics developed an immense popularity. Aware of that, Ghaibeh said, “Syria went as far as banning all comics other than their own comic, Osama.” Other comics had to be smuggled in from Lebanon.

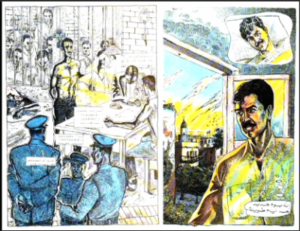

Many Arab dictators also had comics created to celebrate their rule, including the fictionalized Saddam story at right.

Religious organizations saw the utility of comics and also began to sponsor their own. Ghaibeh showed a Maronite comic from Lebanon, as well as a number of Islamic comics from different places on the spectrum, all the way to comics that celebrated suicide bombings.

The era of the state-run comic is now over, Ghaibeh said, with the market now shifting toward independent comics of different kinds. Arabic comics magazines of the past have been reduced to mediocrity, she said. You can really see a decline of state-run children’s magazines.

So what is an Arab comic?

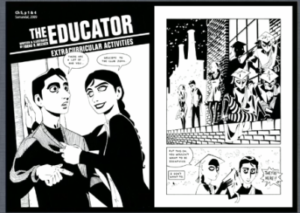

Lebanese comic artists Fadi Baki, one of the founders of the iconic Samandal magazine, and comics artist Fouad Mezher were also at Brown to discuss their work. Interestingly, Baki said that, “Comics in the Middle East happen in spurts; there isn’t this continuous history” as can be found in other comics traditions. What’s more, a Lebanese comic is not an Egyptian comic, nor an Algerian comic. As Ghaibeh pointed out, different countries were influenced by different traditions. Syrians, for instance, were more influenced by Russians, while Lebanese and Algerians more by French comic artists.

Censorship was raised during Baki’s talk. “There is censorship, and it’s something that we’re always worried about…and something that’s hard to talk about.”

Samandal generally avoided sex, Baki said. When they did get in trouble with the censor, they were surprised at what a trivial comment about religion it was.

After the talks, Elias Muhanna suggested that, “In Lebanon, we don’t have this issue with tremendous state censorship, because we don’t have this tremendous state.” Baki responded that. “Censorship is not even coming from the state sometimes. There is this fear..how will they react to a comic?” And, on Twitter, Lebanese literary agent Yasmina Jraissati wrote that “censorship often comes from publishers worried of not being able to sell on other markets, or from authors themselves.”

Baki again: “The state is not necessarily there as a singular state. Instead what you have is sort of anarchy and anyone who has any sort of power will shut you down. So you don’t know where you stand.”

Another thread in the discussion was whether an Arab comic written in French or English was still an Arab comic. In the end, there was no singular representation of what it meant to be an Arab comic, although hope that the Internet has allowed Arab comic artists to “see each other,” and possibly to move forward on different, organic comics styles.

Meanwhile, Egyptian cartoonists spoke to Ahram Online “about truth, utopia and self-censorship.”

“You start thinking of the repercussions of what you draw,” Mohamed Tawfiq, one of the founders of the comic magazine TokTok, told Ahram Online. Tawfiq pointed to the period between Jan. 25 2011 and the end of 2012 as the “richest period” for non-self-censored creativity.

“Exercising self-censorship is not a healthy habit,” Doaa al-Adl told the newspaper, while also saying that, at the current time, “she thinks for long bouts before she draws.”

Also, Egyptian Minister of Culture Gaber Asfour on why Egyptian censorship is the best censorship, among other things.