Why translators deserve some credit

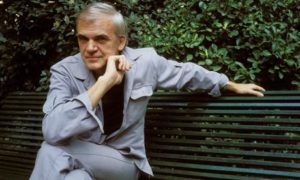

Milan Kundera fears translation could make his style banal. Photograph: Lochon Francois/Gamma/Camera Press LOCHON FRANCOIS/GAMMA/CAMERA PRESS

It’s time to acknowledge translators – the underpaid and unsung heroes behind the global success of many writers

The Observer

Who wrote the Milan Kundera you love? Answer: Michael Henry Heim. And what about the Orhan Pamuk you think is so smart? Maureen Freely. Or the imaginatively erudite Roberto Calasso? Well, that was me.

The translator should do his job and then disappear. The great, charismatic, creative writer wants to be all over the globe. And the last thing he wants to accept is that the majority of his readers are not really reading him.

His readers feel the same. They want intimate contact with true greatness. They don’t want to know that this prose was written on survival wages in a maisonette in Bremen, or a high-rise flat in the suburbs of Osaka. Which kid wants to hear that her JK Rowling is actually a chain-smoking pensioner? When I meet readers of my own novels, they are disappointed I translate as well, as if this were demeaning to an author they hoped was “important”.

There is complicity between globalisation and individualism; we can all watch any film, read any book, wherever made or written, and have the same experience. What a turn-off to be reminded that in fact we need an expert to mediate; what the Chinese get is a mediated version of me; what I’m reading is a mediated Dostoevsky.

Some years ago Kazuo Ishiguro castigated fellow English writers for making their prose too difficult for easy translation. One reason he had developed such a lean style, he claimed, was to make sure his books could be reproduced all over the world.

What if Shakespeare had eased off the puns for his French readers? Or Dickens had worried about getting Micawber-speak into Japanese?

Translation has been even more of an issue for Kundera, concerned his style was being made to sound banal. The translator’s “supreme authority”, Kundera thundered in Testaments Betrayed, “should be the author’s personal style… But most translators obey another authority, that of the conventional version of ‘good French, or German or Italian’.”

Yet deviation from a linguistic norm only has meaning in the context of the language from which it sprang. When Lawrence writes of an insomniac Gudrun in Women in Love that “she was destroyed into perfect consciousness”, he gets his frisson. But what if destruction was understood as a transformation; what if consciousness was seen negatively?

You’ll never know exactly what a translator has done. He reads with maniacal attention to nuance and cultural implication, conscious of all the books that stand behind this one; then he sets out to rewrite this impossibly complex thing in his own language, re-elaborating everything, changing everything in order that it remain the same, or as close as possible to his experience of the original. In every sentence the most loyal respect must combine with the most resourceful inventiveness. Imagine shifting the Tower of Pisa into downtown Manhattan and convincing everyone it’s in the right place; that’s the scale of the task. Writing my own novels has always required a huge effort of organisation and imagination; but, sentence by sentence, translation is intellectually more taxing. On the positive side, the hands-on experience of how another writer puts together his work is worth a year’s creative writing classes. It is a loss that few writers “stoop” to translation these days.

Of course, if the translator is poor there will be awkward moments of correspondence (you get the content but not the style); alternatively the prose will be fluent but off the mark (you get style but not content). The translator who is on song – the one who has the deepest understanding of the original and the greatest resources in his own language – brings style and content together in something altogether new that is also astonishingly faithful to its model.

Occasionally, a translator is invited to the festival of individual genius as the guest of a great man whose career he has furthered; made, even. He is Mr Eco in New York, Mr Rushdie in Germany. He is not recognised for the millions of decisions he made, but because he had the fortune to translate Rushdie or Eco. If he did wonderful work for less fortunate authors, we would never have heard of him.

This is why one has to applaud Harvill Secker for launching a prize for younger translators, one of the few prizes to recognise a translator not because he is associated with a famous name, but for translating a selected story more convincingly than others.

Each generation needs its own translators. While a fine work of literature never needs updating, a translation, however wonderful, gathers dust. Reading Pope’s Homer, we hear Pope more than Homer. Reading Constance Garnett’s Tolstoy, we hear the voice of late-19th-century England. We need to go back to the great works and bring them into our own idiom. To do that we need fresh minds and voices. For a few minutes every year we really must acknowledge that translators are important, and make sure we get the best.

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/apr/25/book-translators-deserve-credit