The Arab whodunnit: crime fiction makes a comeback in the Middle East

The neo-noir revolution in the Arab world might be seen as nostalgic, but it allows writers to act as ombudsmen in the current political climate

Jonathan Guyer

Friday 3 October 2014

From Baghdad to Cairo, a neo-noir revolution has been creeping across the Middle East. The revival of crime fiction since the upheavals started in 2011 should not come as a surprise. Noir offers an alternative form of justice: the novelist is the ombudsman; the bad guys are taken to court.

“Police repression is an experience that binds people throughout the Arab world,” writes Dartmouth professor Jonathan Smolin in Moroccan Noir: Police, Crime and Politics in Popular Culture. That experience of repression did not simply pre-date the 2011 uprisings; it stimulated the revolts themselves.

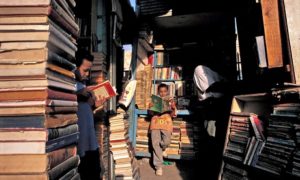

The genre has long been popular in the Middle East though often considered too lowbrow for local and international scholarship. Mid-century paperbacks – shelves of unexamined pulp, from Arabic translations to locally produced serials, along with contemporary reprints of Agatha Christie – languish in Cairo’s book markets. Writer Ursula Lindsay quips: “Cairo is the perfect setting for noir: sleaze, glitz, inequality, corruption, lawlessness. It’s got it all.”

A variety of new productions – cinema, fiction and graphic novels – address crime, impunity and law’s incompetence. Novelists are latching onto the adventure, despair and paranoia prevalent in genre fiction to tell stories that transcend the present. Ahmed Mourad’s best-selling thriller, The Blue Elephant, now showing in cinemas across Egypt, is one of many unsentimental reflections. British-Sudanese author Jamal Mahjoub has also penned three page-turners under the nom de plume Parker Bilal, taking the reader from Cairo to Khartoum.

Enter Elliott Colla. The American scholar has written Baghdad Central, a meticulously researched whodunnit set in wartime Iraq, 2003. With the pacing of film noir, Colla seizes the disorder of the US occupation. American stooges blackmail Muhsin al-Khafaji, a former Baath party operative, into serving as a dick for hire. Haunted by memories and migraines, Khafaji trails his missing niece; she has been snatched, maybe bopped. When the Iraqi detective strolls a university campus that was recently shelled, the anti-hero sees “a row of identical concrete buildings, each suffering an acute case of .50 calibre acne.” Colla is a master of callous narration. I hope an Arabic translation, whether bootlegged or officially licensed, appears on Cairo bookstands soon.

Baghdad Central is a fictional yet hyper-realistic reimagining of justice actually being served in the battle-scarred country. Like post-war America, the golden age of Hollywood’s film noir productions, Baghdad offers an ethereal backdrop. “Setting it in the fall of 2003 is not an accident; this is a moment that is important for us to return to, and this is what the book is asking us to do,” Colla tells Guernica magazine. The novel has new significance as American ghosts and aircrafts linger in Iraq.

The Iraqi detective’s ad-hoc moral code, his willingness to collaborate with the occupiers in order to survive, drives the book’s plot. “The novel is really interested in a moment of ambiguity,” says Colla. “Noir is where the clarity of moral divisions break down, the black and whites turn into greys.”

Ambiguity permeates the genre itself. Scholars have long grappled with a definition for noir. The New Yorker film critic Richard Brody argues that the genre of shadows remains “elusive.” In a recent blog post, he writes: “Film noir is historically determined by particular circumstances; that’s why latter-day attempts at film noir, or so-called neo-noirs, almost all feel like exercises in nostalgia.”

Even as I sort through discarded vintage dime novels in creaky Cairo bookstalls and watch black-and-white Egyptian cinema, I cannot help but think that these pop products are anything but nostalgic. They feel contemporary, not backward looking. If the form is nostalgic, then it represents an unsentimental nostalgia, one that empowers the alienated and the oppressed. For authors and scholars working in the Arab world, neo-noir is an opportunity to critique imported wars, local autocrats and arrested revolutions.

Nostalgia can excavate counternarratives of bygone popular culture. In reading Walter Benjamin, the critic Fredric Jameson finds a theorist radically reinterpreting the past through a constructive prism. “There is no reason why a nostalgia conscious of itself, a lucid and remorseless dissatisfaction with the present on the grounds of some remembered plenitude, cannot furnish as adequate a revolutionary stimulus as any other,” writes Jameson in Marxism and Form.

Just as Benjamin sleuthed the remnants of 19th century Paris for clues of the past, novelists today are looking to Baghdad, Cairo and beyond as archives of memories, places where corruption has privileged certain histories. The crime procedural is a vehicle for inspecting a city’s other histories, its scars and pockmarks.

Jonathan Guyer is a senior editor of the Cairo Review of Global Affairs. He blogs at Oum Cartoon and tweets @mideastXmidwest

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/oct/03/middle-east-crime-fiction-comeback-neo-noir